Our new study proves that only 14% of those who suffered restrictions as ‘infected’ individuals with a positive PCR coronavirus test were actually infected.

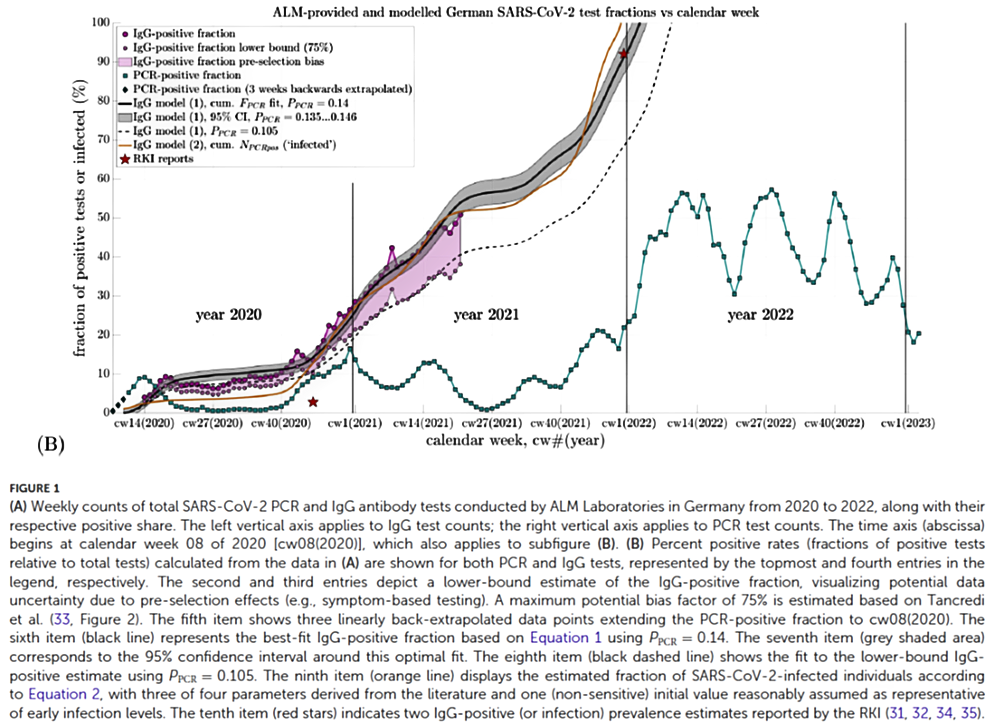

During the unfortunate coronavirus years, we all had to endure nasal or throat swabs followed by PCR tests, sometimes on a daily basis, combined with anxious waiting: Is it positive? Will I now be unable to travel, go to work, university, restaurants or meeting places? Even the German Infection Protection Act stipulates this testing procedure. In our new study [1], recently published in Frontiers in Epidemiology, we show that only 14% of those who tested positive with a PCR test and therefore often had to experience some form of restriction actually had a manifest infection.

This can be deduced from a comparison of data collected with a PCR test and an IgG antibody test. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR), invented by Kary Mullis [2] in the 1980s, for which he received the Nobel Prize, uses tiny snippets of any gene sequence and searches for the matching counterpart in a sample. And if it finds even a single such counterpart, it amplifies it as often as desired and as long as the process is kept running. This works through cycles of repetitions. According to laboratory wisdom, I have been told by specialists, this is normally not done more than 20 times, because otherwise the risk of a false positive result becomes too great. One would then claim that a certain gene sequence was found in someone or in a sample, even though it is not actually there. This so-called cycle threshold, abbreviated CT, is therefore an essential part of a PCR test. This is because it provides information about how often the original sample must be amplified in order to find something. Can anyone remember a CT value being specified on the PCR test that was given to us? No? That’s right. Because it was almost never specified. However, we know from various studies that German laboratories worked thoroughly with CT values of 30 to 35, sometimes even up to 40 (evidence in our publication). Therefore, the risk of false positive results was very high.