Sailing between the Scylla of gullibility and the Charybdis of conspiracy theories in the Corona crisis

Thoughts on Mattias Desmet’s new book, The Psychology of Totalitarianism (London: Chelsea Green, 2022, 231 pages, €32.50, hardcover)

In the corona crisis, one sees two main camps: those who largely believe the mainstream narrative of the coronavirus to be true, and those who question this narrative – sometimes loudly, sometimes quietly. The first group, for the sake of simplicity, I will call below the believers, the others the doubters.

The doubters usually have one major problem: namely, understanding how it is possible that so many of their – quite intelligent – contemporaries subscribe to such an obviously false narrative that the believers believe to be true. I locate myself among this group of doubters. Many in this group then look for explanations and very often end up with one or another conspiracy narrative. Such a conspiracy narrative then explains that some group – the pharmaceutical industry, the financial industry, sinister groups in the backrooms of politics, a Satanist gang, the World Economic Forum (WEF), a secret world government, the “elites” – instigated the whole thing to further their own agenda. I can well understand why people seek such theories as explanations and often find them plausible, but I personally find them rather inadequate as explanations most of the time.

For anyone who feels the same way as I do, Mattias Desmet’s book will provide a welcome new perspective. For it is an important attempt to close this explanatory gap. It makes plausible why there can be such a thing as a coordinated mass phenomenon like the large group of believers without anyone orchestrating this movement in the background. The model, in a nutshell, looks like this:

The model

If anything operates in the background, it is a prevailing background ideology. You can call it, depending on your inclination, scientism – the belief in science; or the mechanistic model of the world – the idea that the world and ourselves work like a machine; or materialistic naturalism – the idea that materialism and the scientific study of matter are sufficient to understand the world.

But if we conceive of ourselves and the world only as a machine that was catapulted into existence by chance out of nothing and is now somehow developing by chance, then the logical consequence is that we conceive of all disturbances, errors or diseases as mechanical malfunctions, which in turn can only be counteracted by mechanical processes: social, political or medical engineering, i.e. social-scientific, political, or medical interventions. This in turn leads to the need to build in more and more control processes, in the social, in the medical, in the political, so that aberrations can be detected early and errors can be traced. Then engineering quality assurance becomes a doctrine. In the end, this ideology of universal steering and controlling leads with dialectical perfidy to exactly the opposite of what is being striven for, namely not to a better life, but to a totalitarian society. That is why the book is called “Psychology of Totalitarianism”. For this reason, we will have to ask ourselves in the future what we want. If we demand security and protection from all the dangers of life from the state, then the price is totalitarian control and thus the extensive surrender of freedom. If we don’t want that, we have to learn to live with uncertainties and endure dangers. The gift is freedom.

The ideology of naturalism has become more and more widespread since the beginning of the Enlightenment and dominates the brains and hearts of many people, especially those in important positions in science, politics, business, the media and perhaps even religions. It leads to people feeling more and more like isolated atoms in a world without meaning or purpose. This gives rise to fear. But this fear has no goal, it just lies there. In psychology, we speak of “free-floating fear”. It leads to frustration and aggression. If this is the case with a large number of people, then this fear will always look for a new object to direct itself towards: Terrorists, Islamists, foreigners, climate catastrophe – or a pandemic.

In such a situation, self-organization processes emerge that lead relatively quickly to new structures, new patterns and new orders – the “new normal” – which then suddenly seem very logical. These self-organization processes seem to be so well coordinated that one cannot imagine them arising of their own accord. But they do in fact arise of their own accord. Towards the end of his book, Mattias Desmet presents a few striking examples from chaos theory that explain how such things work.

And now something important happens: the formerly atomised individuals, each bobbing along in a meaningless and empty world, now suddenly feel a new sense of purpose. And above all: they feel new connectedness with others. All are united in fighting this new threat and something emerges that they have not felt for a long time: a sense of belonging, of connection, of solidarity with others.

This in turn leads to the in-group of believers, similar to the members of religious groups or political parties, feeling good internally and delimiting themselves externally: against the others, the pagans, the unbelievers, the sceptics and doubters. Their arguments, threats against the newly created world view, are thus devalued, no longer find a hearing, no longer penetrate the channels of reporting of the mainstream media, but have to look for side channels.

The consequence

Now this leads to the division of society that has become visible. Most of the time, the believers are in the majority. That was definitely the case in the Corona crisis. Politicians have a good sense of the desire and needs of the majority. They literally sense their desire for new regulations. And they comply with it. So politicians are not the drivers, but the driven ones, because they try to sense the wishes of the majority and act accordingly. This is how lockdowns, compulsory masking, excessive hope in the effect of vaccinations and other therapeutic interventions come about.

The most absurd measures are perpetuated precisely because they help keep fear at bay, and because they flow from the narrative that now makes new sense of the world. Counter-arguments are blanked out and opponents, the doubters and sceptics, are dehumanized. This could be seen in many places on social media. Language is derailing even among very distinguished people.

It also leads to the majority becoming blind to side effects, for example the collateral damage done by the defences against infection, to the vaccine side effects that must not even be mentioned, let alone investigated, if one is not to lose one’s standing among the faithful. It results in the inhumanity that is revealed here being studiously overlooked.

And above all, one overlooks the fact that all these effects and side effects of measures and countermeasures, desired and undesired, have basically always been inherent in the narrative of naturalism. After all, if I see the world and myself as a soulless machine and a biological automaton, then I can’t help but agree to optimization through technocracy.

And so the rule of experts, technocracy, and with it totalitarianism, is the logical consequence not only of this underlying ideology of naturalism or mechanism, but also necessary to deal with the crises thus created. For naturalism implies technocratic management of problems. Where something is understood as a mechanism, one has to intervene when the mechanism is derailed.

In this respect, this is a vicious circle: the ideology of materialistic naturalism alienates people from themselves and from nature, and thus conjures up psychological distress through the resulting fear and isolation. This is directed towards the next best threatening event and forces the political actors to take totalitarian action. This totalitarian crackdown leads to a stronger fortification of the underlying mindset, and thus to a perpetuation of the very mindset that creates the problems.

Totalitarianism is thus the necessary consequence of a purely mechanistic-materialistic understanding of nature, to put it in a nutshell. It is important to distinguish dictatorship from totalitarianism. Desmet spends a lot of care on this. Just this: dictators are only concerned with consolidating their own power. They stop with arbitrariness as soon as this power is secured. Violence is only directed against the opposition. Totalitarianism, however, can also rule in a democracy. It strives to get a grip first on the problem, but then also on the population, which may stand in the way of this grip. In the end, all are to be subservient to the ideology.

What is special about this crisis is that for the first time the whole world has been drawn into this totalitarian maelstrom, because naturalism has become the dominant new narrative after the great religious narratives of redemption have abdicated, at least in the West.

And I add in parentheses – Desmet says nothing about this: the fact that the official Christian churches were caught up in this mainstream Corona narrative shows how deeply they too are already ingrained with this mechanistic naturalistic ideology.

The Sources

Desmet cites Hannah Arendt as the main guarantor of his ideas. The political scientist and student of Heidegger was, as is well known, a main analyst of Nazi ideology, and in her analysis of the totalitarianism of National Socialism she showed how comparatively few people could seduce the masses. The leaders of such a totalitarian regime are as much under hypnosis as they are hypnotizing the masses. Desmet uses historical examples – National Socialism and Stalinism – to show how these processes work. How, in the beginning, comparatively few can put whole masses under their spell, lead to a new organization and, in the end, have a total influence. Even though National Socialism and Stalinism were dictatorships as well, the totalitarian structures were the central mechanisms in these regimes. And because these mechanisms function independently of the political order – in dictatorships, monarchies and democracies alike – it is precisely because of this that totalitarian thinking and action can also take hold in our “free, Western democracy”, as we call it.

The Solution

How can one act in such a situation? The solution cannot be violence in any case. Nor to pay back in kind and react with similar linguistic lapses as the other side you are trying to convince. The solution is to speak. Words trigger hypnosis. Words can also release it. By speaking, writing, discussing, whether in public, at home or at work.

Because: one can assume that at best a hard core of perhaps 30% of the population belong to the true believers. Maybe 40-50% rather are followers. They join in because they want to belong, because they don’t want to stand out, because they see no other solution, because they are afraid for their jobs, or because they expect advantages. They know very well that the mainstream narrative is fragile. These people can be reached and also convinced by good arguments. After all, if the group of sceptics grows, the wind will also change.

Rating

I find this analysis very lucid and helpful. For with its help one gets safely into the open between the maelstrom of conspiracy theories and the cliff of the mainstream’s patently useless narrative. In a way, it also explains its own basis at the end by showing the space for a broader version of our idea of man and science. This bears much resemblance to what I set out in my Galileo report. For what we need is a clear exposure of the naturalist narrative for what it is: as ideology or postmodern materialist religion [1]. There is no need to object to this as long as it is clear that it is a belief and religion. After all, there is freedom of religion. But when this new religion comes in the guise of science, or when the ideology is even sold as science, it is mislabelled.

It is not a model that explains everything. I personally also know people who think the mainstream narrative is correct and in whom I would hardly locate social isolation or existential anxiety, frustration or aggression. There are certainly other processes that play a role in why individuals allow themselves to be carried along by this mass movement. It seems very obvious to me that the above-mentioned conditions give rise to mass formations. That masses and large groups, once they have come together, exert a strong pull can be seen at every football match. In individual cases, one would certainly have to take a lot of motives into account. But Desmet paints the big picture very lucidly with broad strokes, and incidentally also linguistically appealing.

Further ideas and empirical tests

One could empirically test the ideas expressed by Desmet. We recently conducted such a test by examining whether the number of Young Global Leaders trained by the World Economic Forum (WEF) over the last 5 years (more than 2,500) correlates with the strength of non-pharmaceutical interventions in different countries [2]. If a WEF conspiracy were at work, one would expect a correlation during the first phase of the pandemic. We do not see this correlation. We only see a correlation from the second phase onwards, clearly and statistically striking. To me, this suggests that Desmet’s model fits better: The WEF (and other groupings similar to it) is likely to function more like an amplifier or echo chamber in which the new normal becomes organized and rapidly stabilized.

One could also run another test, and this is a call for competent experimenters to take up this cause:

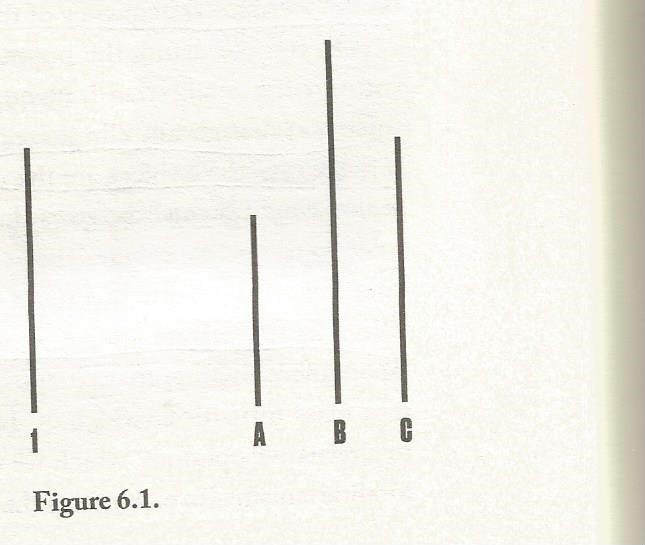

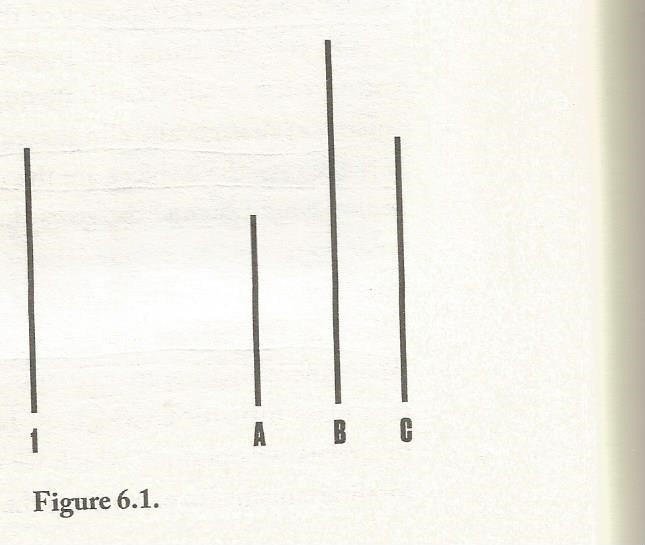

Solomon Asch tried to find out after World War 2 why so many people adhered to this ideology and conducted a famous perception experiment, which Desmet describes in his book on p. 99 [3]. He showed test subjects three lines of different lengths. They were asked to judge their length with respect to a reference line (line 1 in the figure). One of the three lines was the same length (line C). One was longer and one was shorter. The subjects were tested in groups of 8. But only one of them was a real test subject. The other 7 were employees of Asch. The test subjects had to give their assessments in turn. The allies of Asch mostly voted unanimously for a line that was clearly too long or too short. There were also control trials without misjudgements by the allies. Always at the end, the real trialists had to give their judgements.

Of the real subjects, about 25% remained steadfast in their perceptions and gave the correct answer, which was line C. The other 75%, under peer pressure, voted for line B as being the same length. But when asked, only about a quarter to a third of the people who had given line B, i.e. the wrong one as being the same length as the reference line, were really convinced that B was the same length as the reference. The others gave this answer only because they did not want to disagree, but were not convinced.

It is precisely these perhaps 40-50% who are open to argument. Whether Desmet’s model applies can be tested, using a replication of the Asch experiment or a similar experiment.

If you give people beforehand our questionnaire, which I recently presented and which we developed to measure proximity to the mainstream narrative in the Corona Crisis [4, 5], then you would expect that people who subscribe to the mainstream narrative would also conform more easily to the majority opinion in such an experiment, and people who do not subscribe to this narrative would be more likely to stick to their perception.

Conclusion

Desmet’s model is intuitively compelling. Whether it is true or not is ultimately an empirical question. In any case, reading this book, especially for those who doubt both the mainstream narrative and conspiracy theories, is extremely useful. And I would especially recommend it to those who believe that one or another conspiracy theory explains the world to them. You will find another form of conspiracy at work here: that of a powerful ideology against the cultural self-understanding that held sway in the Occident and the West until very recently [1].

Sources and literature

- Walach H. Kulturkampf 2.0: Wie deuten wir die Welt und wer ist maßgeblich. Zeitschrift für Anomalistik. 2021;21(1):185-94.

- Klement, R. J., & Walach, H. (2022). Is the Network of World Economic Forum Young Global Leaders Associated With COVID-19 Non-Pharmaceutical Intervention Severity? Cureus, 14(10), e29990. doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.29990

- Asch SE. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against an unanimous majority. Pschological Monographs: General and Applied. 1956;70(9):1-70.

- Walach H, Ofner M, Ruof V, Herbig M, Klement RJ. Why do people consent to receiving SARS-CoV2 vaccinations? A Representative Survey in Germany. BMJ Open. 2022;12(8):e060555. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060555.

- Walach H, Ruof V, Hellweg R. German Immunologists‘ Opinion on SARS-CoV2 – Results of an Online Survey. Cureus. 2021:e19393. doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19393